Over 30 years of anarchist writing from Ireland listed under hundreds of topics

1913 Lockout in Dublin & Larkinism - beyond the myths

In this article, Donal Ó Fallúin looks briefly at the politics, ideas and misconceptions around the Dublin Lockout of 1913, and shows that the event is much more complex than many have allowed it to be, by attempting to narrow it down to a small event within the nationalist narrative of the period.

In this article, Donal Ó Fallúin looks briefly at the politics, ideas and misconceptions around the Dublin Lockout of 1913, and shows that the event is much more complex than many have allowed it to be, by attempting to narrow it down to a small event within the nationalist narrative of the period.

The 1913 Lockout is a monumental event in the history of the Irish working class. It marks the single greatest confrontation between the forces of labour and capital in Irish history, and the six-month dispute which tore Dublin apart saw a new, militant spirit of trade unionism collide with the force of native capitalism in an unprecedented manner.

It was a dispute during which some workers would lose their lives, and during which international solidarity and the tactic of the sympathetic strike were central to the workers cause. Yet while 1913 features within the state ‘Decade of Centenaries’, as historian Brian Hanley has noted the real irony is that “the Lockout has been sanitized beyond recognition and will be commemorated this year by many who would prefer to ignore the reality of what took place in 1913.”

The article aims to examine the tactics and lessons of the Lockout, and to challenge some of the myths which have grown up around the events. Firstly, it is important to briefly put the event in its correct context, before later examining the role of syndicalism and the idea of sympathetic strike in the dispute. The Lockout is too often spoken of within the nationalistic narrative of the period, but this article aims to show that the event itself, and the broader working class movement at the time, are distinct from the nationalistic narrative of the ‘Irish revolutionary period’.

The Lockout in context:

By the end of nineteenth century, only a small percentage of the Irish working class found themselves within trade unions. As noted in Divided City: Portrait of Dublin 1913, by the time of the first Irish Trade Union Congress there was about ninety-three unions in Ireland, which represented only 17,476 workers. Still, the very foundation of an Irish Trade Union Congress in the 1890s marked an important moment in the development of trade unionism in Ireland. While trade unions succeeded in establishing themselves in the industrial heart of Belfast, Dublin was a different matter entirely. In Dublin, ‘craft unions’ did exist, but these lacked militancy and were often in cosy alliances with employers. Seeking to only organise workers within a particular industry along the lines of the particular craft, these unions differed greatly from industrial trade unionism, and the vast majority of the Dublin working class remained outside of trade unions. It is crucially important to note, as Brian Hanley has, that bosses in Dublin were quite content with craft unions, but rejected more militant forms of working class organisation:

“Murphy tolerated craft unions in his companies, provided they accepted strict codes of conduct for workers. He and his fellow employers made clear on several occasions that they had no difficulty in negotiating with ‘responsible’ trade unions.”

Not alone was a huge percentage of the Dublin working class outside of any kind of trade union movement, but they lived in abject and today almost unimaginable conditions of poverty. The slums of Dublin, and the working conditions of the poor, were truly alarming. Charles A. Cameron, a Protestant Unionist and the Chief Medical Officer for Dublin, wrote in 1913 that “in 1911 41.9 per cent of the deaths in the Dublin Metropolitan area occurred in the workhouses, asylums, lunatic asylums, and other institutions” and he went on to note that “in the homes of the very poor the seeds of infective disease are nursed as if it were in a hothouse.”

There existed a belief too that the shocking conditions of the working class were something they had come to accept, or to see as their “natural lot”, something embodied by the remarks of the contemporary historian and social scientist David Alfred Chart when he noted of the poor working class Dubliner:

“He accepts the one-roomed tenement, with all that the one-roomed tenement implies, as his natural lot and often does not seem to think of, or try for anything better. If he had any real resentment against that system, he would not have elected so many owners of tenement houses as members of the Corporation.”

The arrival of industrial unionism in Dublin and other Irish cities would give many of these people their first real sense of class consciousness. C.Desmond Greaves has written that ‘new unionism’ made its debut in England in 1889 “when the unskilled workers claimed their place in the sun.” By the early 1890s, “the tradesman had been organised, legally or illegally, for over a century, at least in Dublin and Cork.” The beginnings of trade unionism among the mass of the working class however in Ireland marked a significant turning point, and the early twentieth century would bring significant confrontation between workers and employers in Ireland, north and south. Strikes and lockouts became common place, ranging in scale from the great Belfast dispute of 1907 which saw Protestant and Catholic working class dockers down tools and equipment for four months, to the first attempts at working class militancy among precarious Dublin newspaper boys, who took strike action in 1911. Central to this period was Jim Larkin, a Liverpool born trade unionist who would bring a new type of unionism to Ireland in 1907.

The arrival of ‘Big Jim’ Larkin in Ireland. Belfast 1907.

“The consequences of Larkinism are workless fathers, mourning mothers, hungry children and broken homes. Not the capitalist but the policy of Larkin has raised the price of food until the poorest in Dublin are in a state of semi-famine. The curses of women are being poured on this man’s head.” – Sinn Féin president Arthur Griffith denounces Larkin.

There is a danger in history, not least the history of the left, to over-emphasise the roles of individuals at the expense of mass movements. Jim Larkin has become an almost mythical character in the history of the Irish working class, his place in Dublin folk memory in particular well secured. Larkin was a difficult character, with what Emmet O’Connor perfectly described in his biography of him as a “brash personality”, which frequently brought him into confrontation with others within the union movement. Yet Larkin was an incredible organiser and orator, described by Countess Markievicz as almost “some great primeval force, rather than a man.” His effect on the Irish working class, in installing a confidence in them that was lacking before, is immeasurable.

Born on 28th January 1874 in Toxteth, Jim Larkin was the son of Irish migrants. Greaves has noted that the Liverpool Larkin grew up in was a “a hot bed of Fenianism, and it would have been hard for Larkin to escape the nationalist influence”, but an equally important influence on Larkin’s political development was the docks he knew as a place of work. His decision to join the NUDL (National Union of Dock Labourers) in 1901 would change the course of his life to come, as it was in this capacity that Larkin was sent to Belfast in 1907 as a union organiser. In Belfast, a society existed in which Greaves has correctly noted religious sectarianism “had been deliberately fostered by employers to keep the working class divided”, and Larkin was instrumental in the rapid growth of the NUDL in the city, growing to 4,000 members and with three offices to its name by late April 1907.

When dock workers in Belfast would strike for union recognition, Larkin succeeded in bringing out a wide range of Belfast workers in solidarity with them, including women from the city’s largest tobacco factory. The sympathetic strike tactic, which would bring out workers not directly involved in an industrial dispute in solidarity with other workers, and Larkin’s tactic of ‘blacking’ goods (with workers refusing to handle goods that were deemed tainted by scabs), represented a new kind of radical trade unionism in Ireland. The strikes even led to an unprecedented police mutiny, when a ‘More Pay’ movement within the police force took action demanding increases in their salaries. The Belfast strike of 1907 represents a very significant moment in the history of the Irish working class, because as John Gray has noted:

“When we look at the 1907 Dock Strike in Belfast and the police mutiny of the same year simple myths begin to evaporate. We find unskilled work- ers, mainly Protestant, fighting the employers, many of their future leaders in the UVF, we find policemen, many Protestant, mutinying.....”

This incident, six years before the Lockout, showed the abilities of Jim Larkin as a union organiser and working class militant, and was terrifying the employers across the island. Not surprisingly, Larkin was dismissed from the NUDL for his militancy, which led to him forming an alternative union, which would become the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union, and subsequently, his later union activities in Dublin.

Larkin, William Martin Murphy and Dublin.

In his history of Dublin tramworkers historically, Bill McCamely notes that the Dublin of the early twentieth century presented Jim Larkin with three important employments he would have dearly liked to unionise. In the case of Dublin Corporation and building workers, these men enjoyed their own unions, albeit unions which were far from radical. Guinness, a huge powerhouse of industry in Dublin also appealed to Larkin as a potential base, although these workers enjoyed working conditions and benefits which made the workforce content, many argued. It was in the Dublin United Tramways Company that Larkin found his target, as this was an industry which had seen off multiple attempts at unionisation, and which contained a hugely significant body of unorganised workers in the capital.

The trams were owned by William Martin Murphy, one of the leading capitalists in the Dublin of the day, and an incredibly complex character. In Murphy alone one of the great contradictions of the popular narrative that exists around the Lockout is found. While some speak only of the event as a sort of ‘dress rehearsal’ for the Easter Rising, and a confrontation between ‘Irish workers’ and ‘British business’, Murphy himself was an Irish nationalist. Indeed, Murphy was even a former Irish nationalist MP, who had actually refused a Knighthood from King Edward VII, on the grounds that Home Rule was denied to Ireland. Murphy was a man of charity but also a ruthless businessman, who built a commercial empire on an almost unprecedented scale in the city. Padraig Yeates has estimated that at the time of his death “he had accumulated a fortune of over £250,000, had built railway and tramway systems in Britain, South America and West Africa, and owned or was a director of many Irish enterprises, including Clery’s department store, the Imperial Hotel and the Metropole Hotel.” Crucially important to the story of the Lockout however was Murphy’s press empire, which included the Irish Independent, the Evening Herald and the Irish Catholic.

When workers in Murphy’s tram company demanded union recognition and waged industrial action, he responded by ‘locking out’ all workers across his business empire who were affiliated to Larkin’s unions, and other Dublin capitalists followed in his footsteps. This is crucially important to the story of 1913. While slogans like ‘1913: Lockout – 2013: Sellout’ have become common place on the left in this centenary year, it is important to stress that the industrial dispute in 1913 was a bosses offensive, and not something instigated by the workers. Murphy took aim at what his media empire termed ‘Larkinism’, and Larkin took aim at a man he believed embodied all that was wrong with the capitalist class.

What was ‘Larkinism’?

A word which has vanished from Irish political and trade union discourse today is ‘syndicalism’, although it was central to debates at the time. William Martin Murphy’s Irish Independent repeatedly attacked syndicalism, for example upon its front page on September 21st 1913 which showed a worker blindfolded (with the blindfold reading ‘syndicalism’) while his family begged him to return to work. Murphy frequently lambasted the concept in his speeches, but what did it mean and why did it cause such fear among Dublin’s leading employers and more even conservative trade unionists? Condemned as ‘Larkinism’ in the Irish press, John Newsinger writers in his work Rebel City that:

“It was a revolt against the authority of the employers, a rejection of the place the working class had been given in society and it contained within it elements capable of developing into a coherent challenge to the employing class and the capitalist system. Certainly, this is what well-informed contemporaries believed”

Larkin believed in the power of the ‘One Big Union’, and that industrial action could be the primary means by which the working class could overthrow capitalism. Speaking towards the end of the dispute, Larkin stated that:

“The employers know no sectionalism. The employers give us the title of the ‘working class’. Let us be proud of the term. Let us have, then, the one union, and not, as now, 1,100 separate unions, each acting upon its own. When one union is locked out or on strike, other unions or sections are either apathetic or scab on those in dispute. A stop must be put to this organised blacklegging.”

Central to the radical political philosophy of Larkin was the sympathetic strike, something James Connolly would describe as “the recognition of the working class of their essential unity.” There are numerous examples of this tactic being utilised during the dispute, for example at Easons when dockworkers refused to handle any goods addressed to the company after Larkin had come into conflict with it. While widely condemned in the establishment media at the time, there was great truth in the words of one independent observer who wrote at the time of the hypocrisy of employers who condemned the sympathetic strike, while “they had no qualms of conscience in having recourse to the sympathetic lockout.”

Larkin’s ideas and tactics are diminished today by trade union leaders who argue that ‘different times call for different tactics’, and incredibly at a recent memorial service for Jim Larkin in Glasnevin Cemetery, Jack O’Connor of SIPTU spoke of how his union refusing to mount a fightback to austerity was somehow in the tradition of Larkin, noting that:

“Of course, once war was declared, Jim Larkin fought to win with every morsel of his being. Yes he was a revolutionary socialist, a syndicalist who aspired to the transformation of society along egalitarian lines. But the reality was that, no less than any leader, and he was a brilliant leader, he would not choose to lead vulnerable men and women and their families into a head-on collision with over-whelmingly superior forces.”

Syndicalism, in the words of historian Emmet O’Connor, “remains the most underestimated andunderestimated and misrepresented ideology ever associated with Irish trade unionism”

Was the Lockout a failure for the union movement?

Undoubtedly, the dispute which dragged into 1914 can only be described as a failure for the organised working class in Ireland. Yet there are lessons which can be learned from the dispute and the approach of the left to it. One aspect of the period and the struggle the left has tended to overlook is the role of media in the dispute. While the Irish Independent and Murphy’s other outlets were able to attack Larkin and the union movement, Larkin succeeded in bringing socialist politics to a very significant percentage of the Dublin working class through the Irish Worker. Established in 1911, C. Desmond Greaves has noted that while the huge circulation Larkin claimed this paper enjoyed is almost certainly not true, even very reasonable estimates from the time show us the mass audience the primary trade union paper reached. While Sinn Féin’s nationalist newspaper had a circulation that fluctuated between 2,000 and 5,000, Larkin’s paper enjoyed a healthy readership, with up to 25,000 copies a week being sold during the dispute.

Early in 1914, huge chunks of the Dublin working class crawled back into employment, even pledging to distance themselves from ‘Larkinism’ in the future. As Greaves has noted though, one of the key effects of the Lockout “on the workers of all industries was to strengthen their consciousness of themselves as a class”. The incredible solidarity shown during the dispute, not only from other Dublin workers but also those further afield who sent crucial economic support, is an inspirational part of the story. The Irish working class would reassert themselves on several occasions during what is broadly termed the ‘revolutionary period’ in Irish history. For example during the show of strength against conscription in 1918 when workers across the island downed tools and equipment in protest at imperialism and war.

Yet the state which emerged from independence did not honour any of the promises that had been made to the Irish working class by mainstream Irish nationalism during its years in revolt. The suppression of labour disputes in a newly independent Ireland demonstrated how for the working class in Ireland, little changed after 1922. Indeed, it is difficult to disagree with the conclusion historian Cathal Brennan draws in his study of the 1922 postal strike (the first significant strike the new Irish state faced) where he writes that:

Despite the attainment of a sovereign, independent state (for the twenty – six counties at least) the aspirations contained in Dáil Éireann’s Democratic Programme of 1919 seemed as far away as ever.

The Lockout must not be seen only as a part of the nationalist narrative of the 1912-23 period, but as the most significant confrontation between labour and capital in Irish history. Whether that confrontation occurred under a British flag, or the flag of an independent Ireland, is irrelevant to the class struggle that was central to the story. The spirit of Dubliners and others who fought back so bravely in 1913 should inspire us today, but it must be remembered that in many ways 1913 is unfinished business, in an Ireland where some workers even lack the right to workplace union recognition today.

Information on the author: Donal Ó Fallúin is a historian, co-author of the blog and book, Come Here to Me and a contributor to the podcast “1913: Unfinished Business” http://ub1913.wordpress.com/

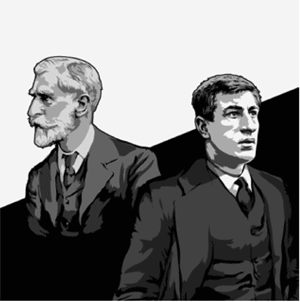

Attribution for the Murphy/Larkin image - Moira Murphy

This article is from Irish Anarchist Review no7 - Spring 2013