Over 30 years of anarchist writing from Ireland listed under hundreds of topics

Was winning the Repeal referendum inevitable?

The vote to remove the ban on abortion from the Irish constitution in May 2018 was overwhelmingly carried, with almost 2 out of every 3 voters voting Yes remove the ban. The margin of victory was such that some post-referendum polemics made the mistake of arguing that victory was always inevitable, that the campaign didn’t matter. Such arguments tended to be made by opinion writers who never liked the Repeal campaign and in some cases published pieces during the campaign arguing that unless whatever aspect they disliked was dropped the referendum would be lost. Opinion that the referendum would always be won has the danger of solidifying into uncontested fact, and that would seriously undermine future understandings of how a similar referendum might be won.

In this piece Andrew Flood who tracked and reported on polls throughout the referendum campaign presents a different opinion, one based not on certain victory but on polls consistently showing that while the Yes campaign could be sure of a vote in the region of 40% anything above this would have to be won or at least retained. And in the context of the failure of previous referendum campaigns to do just that the scale of the 66.4% yes victory in May is something that can surely be learned from.

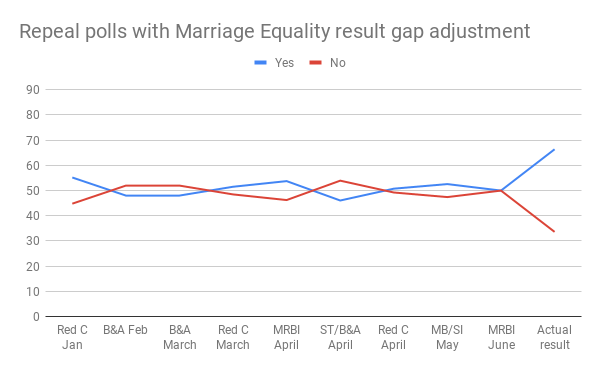

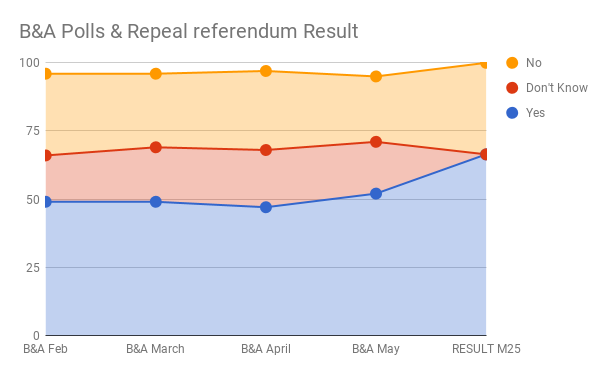

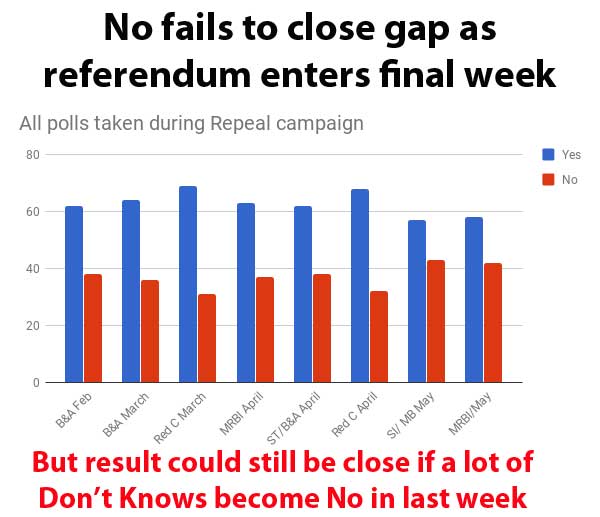

In summary I’m going to show here that while opinion polling had been indicating for some years that a referendum could be won this was no guarantee of victory, especially when you take into account the previous anti-oppression referendums that removed the ban on divorce and allowed marriage equality. Both these saw a major drop in support for change in the closing 10 days of those campaigns, almost leading to defeat in the 1995 divorce referendum And as the graph that takes this drops into account suggests a similar drop in May could even have seen Repeal lost. Opinion polls suggest we could be certain of a Yes vote around 40%, anything much above that would have to be won/retained by a campaign that was more successful than the 1995 Divorce and 2016 Marriage Equality ones.

How the Repeal polls looked when you applied the adjustment for the reduction in the Yes vote in Marriage Equality polls

Certainly those central to the Yes campaign were very aware of this and in many cases not confident of victory until the very last couple of days of the campaign. A some not really confident until the publication of both exit polls shortly after the polling booths closed. There fear was that if the No campaign could create enough Fear, Uncertainty ands Doubt they would repeat the last minute success of the No to Marriage Equality campaign and succeed in pushing most of the Don’t Know vote in the opinion polls into a No vote on polling day. That was very much the strategy of the No campaigns and why in the final 10 day period they shifted much of their messaging from an absolutest anti-choice No to the suggestions that the specific proposals were too extreme and people should vote No so that the government would be forced to produce better proposals.

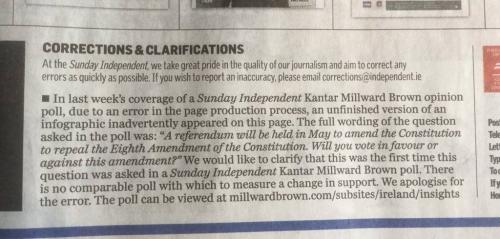

No campaigners online were looking for and then talking up any apparent reduction in the Yes vote as the start of the collapse seen in the other two referenda. There was even a very grim moment when it looked like they had succeeded. In the first week of May the Sunday Independent incorrectly presented a comparison between an opinion poll asking people how they would vote with their February poll asking if there should be a referendum. This was presented as a large drop, 18%, in the Yes vote and came at the point where those of us aware of the previous Divorce and Marriage Equality drops were worried we’d see the start of just such a decline. A drop of sufficient size in fact to make defeat likely, and certain if it represented a trend that would continue. There were a glum few days until the Independent printed a completely inadequate correction buried inside the paper in print far smaller than the original graphic.

The correction that appeared in the Sunday Independent

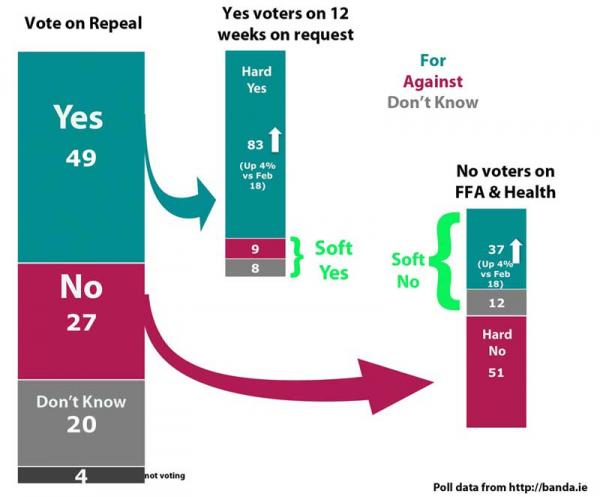

At the start of the campaign in March I wrote a long piece that sought to use the opinion polls to draw some tactical conclusions around likely voting patterns in the referendum. Overall this holds up well but for this piece I want to focus in on one particular area, how large was the definite Yes vote at that point in time.

The Sunday Times / Behaviour & Attitudes March poll (p13 to p17) directly asked those polled on their attitudes on two abortion access related questions that the referendum centred around. This gives us an idea of how certain people were in there voting intentions that was not reliant on self-reporting after the fact. One question was whether abortion should be available for any and all reasons up to 12 weeks. The other whether it should be available for the ‘hard cases’ of threats to health and Fatal Foetal Abnormality where the baby would either be stillborn or die soon after birth.

More people were willing to support this second case than were also willing to support the first case but the promised legislation would deliver abortion access for both cases. So we could say that the Hard Yes voters were those who answered Yes to abortion access in both cases while the Hard No voters were those who answered No in both cases. Both these groups were unlikely to be swayed in the campaign. On the other hand there were people who wanted abortion access in one case but not the other, these soft Yes/No voters and the Don’t Know voters were the people whose mind could very well change over the course of the campaign.

Using the March 2018 B&A poll to illustrate the hard and soft votes on the 12 weeks and health questions

That March poll showed these broke down as below;

40% hard yes (‘its a women decision’)

8% soft yes (‘for health threats & FFA only’)

20% Don’t know

4% Not voting

14% soft no (‘but should be available for health & FFA’)

14% hard no ( ‘not even for health & FFA’ ).

That 40% hard yes was consistent with opinion polls over recent years that showed a steady rise in the number saying that abortion would be the women choice, in 2013 this had risen to 37%, it was only half that in 1997. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/big-rise-in-support-for-legislation-on-a...

For both sides the aim of the campaign was to mobilise there own hard voters to go out and vote (and perhaps canvass). But more importantly to make sure as many of their soft voters did actually vote, win over the Don’t Know and either win over the other sides soft voters or at least discourage them from voting, In particular since the protests following the death of Savita the issue itself had been widely and consistently discussed meaning those for or against abortion access in both of the cases above were unlikely to be swayed by arguments they heard during the campaign.

So the three key groups to whether the referendum would pass and by how much were;

1. The ‘soft Yes’ voters who were voting yes but unsure about aspects of a women right to choose. Typically this 8% of voters only wanted women to be able to access abortions for some reasons and not other..

2. The Don’t Knows that had not yet decided how to vote but who did intend to vote. Although you might expect a lot of this group of 20% are the people who won’t actually vote previous referendum data indicated they were only slightly less likely to vote then those who knew how they were voting early on.

3. The ‘soft No’ 14% who were against a women’s right to choose to 12 weeks but thought there are some circumstances eg Fatal Foetal Abnormality (FFA) where access to abortion should be granted.

The above figures suggest that 44% of the electorate were the main targets of the campaign messaging from both sides. Yes started off stronger and only needed to convince 1/4 of that 44% to get 50%+1. But the historical pattern from Divorce and Marriage Equality was for No to take all or almost all of these groups - an outcome that would have led to the defeat of the referendum or at best the narrowest of victories. A narrow victory might have been almost as bad as a defeat, the legislation introduced on the basis of a 2:1 win is far from perfect and contains medically meaningless concessions to anti-choice TD’s including the 4 day waiting period between the first visit to the doctor and the return four days later. We can only imagine the concessions that would have been given in the event of a narrow 51% victory, there is a high chance the resultant legislation would have been close to worthless, containing so many tests and barriers that women able to travel would continue to do so.

Two previous examples

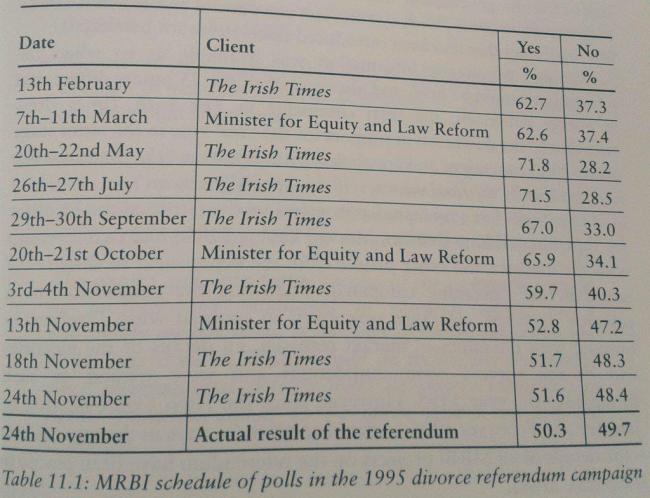

The 1995 Divorce referendum looked to be safely in the bag from advance polls with a 2:1 lead but on the day was only narrowly carried 50.3% Yes to 49.7% No. A result so close that its said the difference was only one vote per polling box in the country. In fact with Don’t Knows excluded the opinion polls ahead of the Divorce referendum were giving Yes & No votes of similar percentages (around 68%) as the polls ahead of the Repeal the 8th referendum.

The 1995 Divorce polls showing the collapse of the Yes vote. Note that the Irish Times poll 6 days out and the exit poll are highly accurate suggesting the earlier polls probably also were and the collapse in Yes was real.

In the closing two weeks of the Divorce referendum it appears that almost all the Don’t Know’s and soft Yes voters opted to either vote No or stay at home. If the same happened with Repeal we’d have lost or have had the narrowest of victories.

Marriage equality

The 2016 Marriage Equality referendum saw a very similar pattern, indeed an even more worrying one as between the polls published the weekend before the vote and the vote itself for all four polling companies the vast majority of Don’t Know’s switched to No voters and in two polling companies cases so did some of the Yes voters. Marriage Equality was polling way above Repeal so that the large drop in Yes voters still saw it pass by a decent margin (62%). When we calculated what a similar drop for each polling company would look for Repeal rather than the polls then predicting a solid victory some predicted a narrow defeat and some a narrow victory. In the lead up to the Repeal campaign Marriage Equality was presented as the gold standard in how to win a referendum so this fear of a similar switch from Don’t Know to No was a very responsible assumption to work off.

|

Marriage equality as of May 16/17 |

SBP/RedC 11-13 |

SI/MB 2-15 |

ST/B&A 1-11 |

IT/MRBI 13-14 |

|

RESULT |

|

Yes |

67 |

53 |

63 |

58 |

|

62 |

|

No |

27 |

24 |

26 |

25 |

|

38 |

|

Don't Know |

6 |

23 |

11 |

17 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Excluded removed |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

71 |

69 |

71 |

70 |

|

62 |

|

No |

29 |

31 |

29 |

30 |

|

38 |

|

|

MRBI Jan |

Red C Jan |

B&A Feb |

B&A March |

Red C March |

MRBI April |

ST/B&A April |

Red C April |

|

Yes |

60 |

55 |

48 |

48 |

52 |

54 |

46 |

51 |

|

No |

40 |

45 |

52 |

52 |

48 |

46 |

54 |

49 |

Table shows the results of each companies polling on Repeal when adjusted by how far they were out from the result for Marriage Equality

The polling companies also expected this with to happen and some tried to build in mechanism to predict it by asking for instance how people thought the vote would go as well as how they intended to vote.

The Behaviour & Attitudes polls when you excluded Don't Knows were consistently close to the result. They can also be read, as above, as showing the swing from Don't Know to Yes in the last days of the campaign

Other worries

As if the comparison with the last week drop in the Yes vote in Divorce and Marriage Equality wasn’t bad enough there were two other important elements that suggested the actual Yes vote on the day could be lower than what was seen in the polls.

The first of these was the enormous differential in voting intentions between age groups. That March B&A poll had only 18% of those in the 18-34 age group voting No but 37% (a narrow majority, Yes was 36%) of those in the over 55 age group. Historically a much higher percentage of older people actually vote than younger people which in the referendum would have boosted the No vote significantly. The poll asked about intention to vote and indeed while 60% of 18-34’s felt they would definitely vote 80% of the over 55s - the one bloc likely to vote No - felt they would definitely vote. Incidentally the differential turn out by age group probably got both Trump & Brexit the votes needed to win, something we were quite aware of at the time.

The second was interpreting the very much higher Don’t Know that was seen in that B&A poll in rural areas as against the cities and Dublin in particular. The Don’t Knows were highest in the regions where the Yes campaign might be weakest, in March they were only 11% in Dublin but 30% in Connacht/Ulster. While we hoped this might indicate that the ‘shy vote’ presenting as Don’t Know would shift more heavily to Yes than No because of the long term reliance of anti-choice movements on public shaming tactics this also meant that a very large proportions of the Don’t Knows were located in areas that in March lacked a Yes campaign and which at that stage looked difficult to canvass and convince.

Also worth mentioning is that the campaign was won despite the non-involvement for most of it of the government that actually called the referendum. It’s forgotten now because Leo stepped into the spotlight when then result came in at Dublin castle but until the last couple of days Fine Gael was almost entirely absent from active campaigning with the exception of Health minister Simon Harris, Kate O’Connell and a few more junior figures in the party. As last as May 22nd, even in Dublin, local Fine Gael organisations were only making contact with the local T4Y groups to offer to help with canvassing.

The graphic accompanying one of our last poll reports, in fact the final Yes vote of 66.4% was higher then most polls indicated

n the end the result at 66.4% was almost exactly what the polls had predicted throughout the campaign. There was no last minute collapse of the Yes vote, in fact it rose. When you compare the results with the polls Don’t know’s were twice as likely -more in some polls - to decide to vote Yes than No. The historic pattern was broken by the Repeal campaign, but why?

Why

The purpose of this piece is not to work out why the Repeal referendum campaign successfully avoided the Yes vote collapse that characterised the Marriage Equality and Divorce referendums, more to point out such an investigation might be very useful for the future. We are slowly working on a detailed collective history of the campaign that will also touch on some of the more negative aspects. But here are some speculative pointers to why the victory was so unexpectedly large.

Silent yes

To take the why literally we can say that there was a large silent Yes, unwilling to disclose to pollsters & canvassers what their true voting intention were. This tended to be largest wherever the No campaign was the best organised and most vitriolic. They thought they had bullied people into silence, and to an extent they had. But when they were in the ballot box those people struck back. The campaigns during the referendum ensured this vote was not eroded and to an extent while this was obviously the achievement of the Repeal campaign the nastiness of the No campaign probably also contributed to getting Yes votes out and suppressing the soft No vote.

Mass involvement in Yes campaign

Probably most important in winning over the Don’t Knows, holding the soft Yes vote and perhaps helping to ensure a lot of soft No’s stayed home was the mass nature of the Yes campaign. But that nature needs to be understand in terms of not only what was required to win the referendum but to force the Fine Gael government to call it in the first place. There was a continuous process of grassroots organisation and movement building led by the Abortion Rights Campaign from the time of the death of Savita in 2012. This meant even before the referendum had been called tens of thousands had marched demanding it and a network of groups and individuals existed across large swathes of the country who had already been working together. It also meant there was an existing structure of Facebook page and Twitter accounts that many people who might be willing to donate and campaign were already part of which made them easy to reach as the campaign launched.

In conjunction with this the referendum itself saw a semi spontaneous upsurge of people getting involved in campaigning. Many of these were not new to struggle but had previous organising experience in all the big struggles over the last decades. I saw friends step up who’d mobilised to try to stop the refuelling of US war planes at Shannon in 2003 and those that had travelled to Rossport along with those currently involved in the militant end of the housing struggles. In the early days of the campaign some of the key organisers for Together for Yes groups around the country were people I knew from these struggles and they brought their skills and networks with them. A sense of the energy and organisation that won the campaign can be got from An Ode to ARC.

Disastrous No

The No campaigns despite or perhaps because of the huge backing in US dollars and their importation of US experts could hardly have done worse. John McGurk in particular was the gift that kept on giving to building a Yes campaign from his clownish attempt to spread a crude fascist smear in the opening days of the campaign to his fake nurse and the constant and increasingly desperate search for a magic gotcha moment. You can get a measure of the role he played in mobilising Yes activists by looking at the comments left as people donated for posters in the Together for Yes online fundraiser. Each small donation, and there were over 10,000 of them, could include a comment and a remarkably high proportion of them mentioned John by name. But he was only the worst of a bad bunch, all of their spokespeople came across as disingenuous creeps seeking to reimpose the sort of judgmental clerical rule we are only in the process of escaping, Ronan Mullen also deserves special mention in that respect.

To an extent the early start of the No campaign, which launched a good month ahead of the Yes one, and the visibly huge amount of cash they had to spend on billboard ads backfired on them. In effect it gave the people who would become the Yes activists a whole month of seeing the sort of financial power they had and the scale of the challenge in defeating that. The effect of that is seen with the enormous rapid response to the Together for Yes online funding campaign to pay for Yes posters. The initial 50,000 euro target was exceeded in just two hours and 12 hours later 250,000 had already been raised. Far from then facing the problem of finding people willing to put posters up the Yes campaign they had the ongoing problem of finding ways to get enough posters to people all over the country often angrly wanting to know why they had not arrived yesterday. In rural Ireland in particular vast numbers of these posters were torn down by organised anti-choice gangs shortly after they were put up but arguably even this backfired as a very visible illustration of the bullying, anti-democratic nature of the No campaigns.

Repeal was probably winnable from 1992 on but winnable at any point up to and including May 2018 wouldn't have meant automatically won in a referendum campaign. A 66.4% yes was a very clear win, but the bigger achievement was probably forcing Fine Gael to call a referendum in the first place. Once called it was essential it was won, almost a decade passed between the first unsuccessful attempt to overturn the Divorce ban and the second successful one. It’’s likely defeat would have seen us facing a decade long struggle for another referendum and without the success of the Yes campaign in convincing those Don’t Know’s to vote yes that might otherwise be where we are today.

Andrew Flood (follow Andrew on Twitter)

The photos from Dublin castle the next day would see scenes of joy as the result become official but the overwhelming initial reaction at Together for Yes HQ when the exit poll was announced was relief. Right to the last minute few were sure of victory.